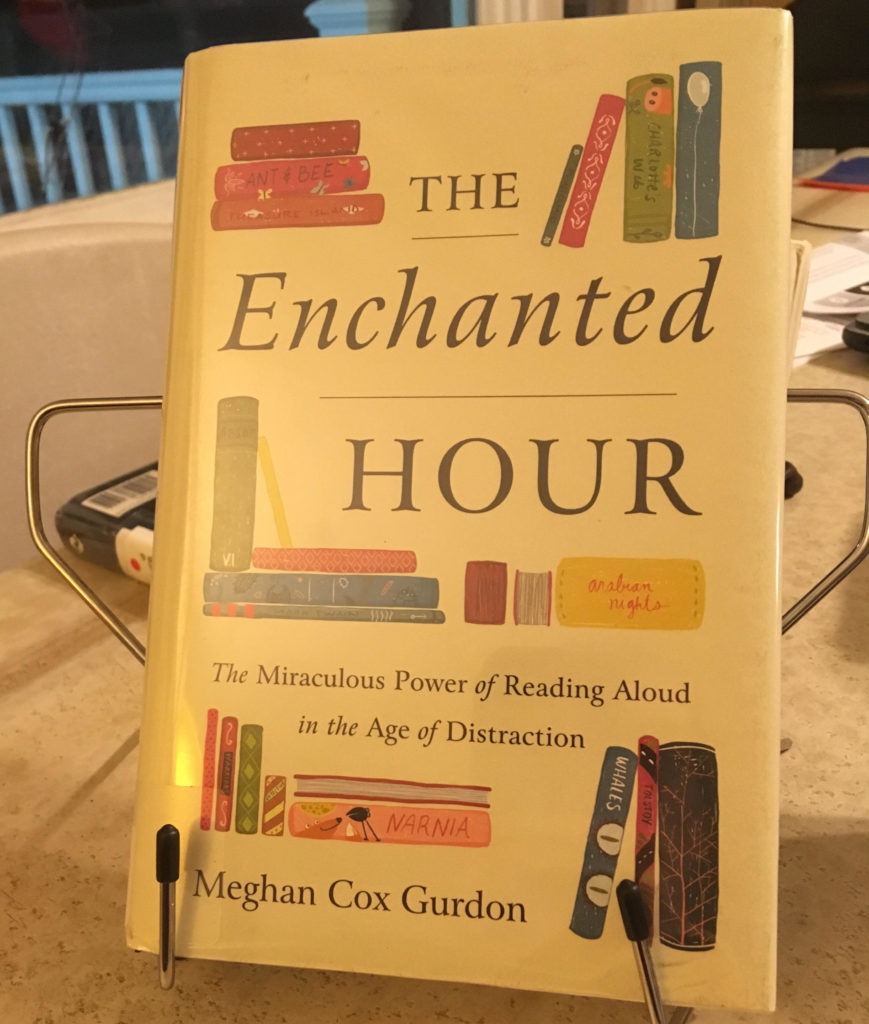

TL;DR version: It’s a good book, worth a read. But it also has some white supremacy issues that it doesn’t handle well. I’d give it five stars if it had handled this issue better. And there’s a really nice booklist in the back. It’d have been better if the list were more fully annotated (children’s book titles aren’t very descriptive!), but you can’t have everything.

Well, now that I’ve written that summary, you’re probably like, “Uhhhh get to the second part.” Because you don’t just make a statement like that lightly.

Let me be clear: I’m not making that statement lightly. I think this is a serious issue, and I think that pretending the issues in this book are not a big deal is part of the problem in our society at large and in this book on a more micro-scale.

And I’ll also be clear that I think this is completely unintentional on the part of the author. That’s exactly why it’s a problem: this is an issue in the structure of our society that this book will unintentional reinforce. Say it with me: even good people can do racist things, even good people can unintentionally support white supremacy. Racism, and white supremacy more broadly, are not the realm of solely “bad people.” We have breathed this in since birth, and it is really hard to deprogram, and you probably will never deprogram it all even if you live a very long time. Every antiracist advocate, especially the white ones, is fighting this battle every single day, and we will all make mistakes. I think this author really thought she was giving good advice to prevent racism in kids. But she wasn’t. Bigotry is measured by impact, not intention. Intention is, quite frankly, irrelevant.

The Big Picture

Overall, the book is good. It’s about the value of reading aloud to children, even those who are proficient readers, but also delves into why reading aloud is good for humans of all ages. Specifically there’s a lot of nice content about reading aloud to the elderly or infirm. But I bet it’s going to preach to the choir rather than convert many people. Still, it’s good chizuk for those who already value reading and maybe help them/us read aloud a little more. For lack of a better term in English, chizuk means it gives you strength, supporting you. I’m just skeptical that someone who doesn’t already read to their kids regularly is going to pick up this book. But I’d love to be proven wrong.

The Problems:

In a nutshell, here is the problem. She talks a lot about how to handle “problematic” books, specifically those that we now socially recognize as racist or having racist content (yay progress of a sort). Her “solution” is simple: read it anyway because it’s good literature and talk about it with your kids. Racism: solved! My problem with this answer is two-fold:

- She doesn’t acknowledge at all the idea that the racist or other bigoted comments might apply to the children involved. Where is the advice to parents when the language applies to the kid hearing it? This advice only acknowledges the issues of white parents of white kids. It is a huge, massive, yet not surprising, blind spot.

- The answer is that parents should talk about it with their kids, but studies (and my life experience) show that white people do. not. talk. about. race. Even more so with their kids. And going back to the first problem, it ignores the fact that parents of color and all minority-group parents (Jews, LGBT, Muslims, whatever) have to have these conversations whether we want to or not, at least when it applies to our group. Plenty of parents ARE having these conversations, but that’s not who it sounds like she’s talking to. Parents in minority groups don’t have to be told to talk about problematic content; that’s a basic survival strategy. It is a fundamental part of white privilege to be able to choose to skip these conversations. People without privilege don’t have the choice.

Let’s talk about this in more detail.

Her solution doesn’t take into account kids who are the subject of the dehumanizing language. And let’s be clear: bigoted language is, at its very heart, dehumanizing. That is its purpose in the philosophy of white supremacy. Her characterization of the problem is very detached: these are ideas we don’t want to expose our kids to. But what if you’re a Native American reading Little House on the Prairie, a text she gives as an example of great literature you shouldn’t put aside because of problematic content? Her writing seems clearly, to me at least, to be addressed to white parents of white kids. I doubt she intended to do that, but that’s the insidious nature of the white supremacy ideas we’ve breathed in since birth in America: white is the default and it’s rare for people, particularly white people, to remember or even see that there’s a different perspective on an issue. She only sees it from her own perspective.

The talk she’s advocating is this:

“We do children no service in cutting them off from transcendent works of the imagination, even if it means introducing them to troublesome ideas and assumptions, and to characters we would rather they not admire [do minority kids risk admiring characters who dehumanize them??]. Like life itself, literature is unruly. It raises moral, cultural, and philosophical questions. Well, where better to talk about these things than at home? The human story is messy and imperfect. It is full of color and peril, creation and destruction – of cruelty and villainy, prejudice and hatred, love and comedy, sacrifice and virtue. We needn’t be afraid of it. It’s foolish to cover it up and pretend history never happened [she forgets: and is still happening and affecting lives today]. It is far better to talk about what we think of these matters with our children, using books as a starting point for conversation.”

“Great art has often been made by bad people,” says the writer and provocatreuse Camille Paglia. “So what?” p172 (emphasis mine)

There are so many problems here, and it goes to both of the issues I identified above. It’s one thing to talk these issues over as a philosophical/history tale. It’s another to read Shylock to your child when you’re actually Jewish. Or about “bloodthirsty savages” when you’re Native American. Or the many and varied horrible stereotypes of Black people. Or any other group you can imagine. Those words dehumanize the child sitting in front of you. And this book has zero advice for how a parent should handle that situation, when the kid says, “But Mommy, I’m not like that. Are we bad people?” Does that work still feel “transcendent” to you when it says dehumanizing things about you? This is a huge problem facing so many parents in America, but this book completely ignores the problem and focuses on the perspective of a white parent of a white child. I certainly have no idea how to answer my child when we will inevitably come across casual antisemitism in a book, and some advice would be great, honestly.

But the biggest point of all: it’s been proven again and again that white parents do. not. discuss. race. White fragility strikes even the best of us. We literally begin to sweat, our hearts race, we may even shake from the anxiety of it. I still do, every single time I talk or write about race. My body physically tries to stop me from doing antiracist work, that is how deep white supremacy goes…into your very bones. But if you’re not actively doing antiracist work in your own life and social circles, then you are part of the problem. White supremacy does not need you to be actively racist. It just needs you to be complacent, even better if you’re “overly polite,” as I used to describe myself. (One of the best things you can do as a white person is read White Fragility by Beverly DiAngelo.)

The same liberal “I’m one of the good ones” white parents who will openly challenge the gender roles books portray, or even religious stereotypes, will either skip these books entirely or read them without real commentary. Maybe, at best, a “that’s not a nice thing to say about X people.” Then quickly move on to something else. Ask me how I know.

The book NurtureShock has a whole chapter on this that’s excellent. And it gives the best example that I remember seeing in real life so many times. I even have a vague memory of it from my own childhood. A white toddler in a grocery store points at a Black person and says, “Mommy, that person’s skin is brown!” The mother says, “Shush!” and maybe “I’m sorry!” to the other person, then pushes the cart away as quickly as physically possible with a broken, squeaky wheel. Red-faced embarrassment all the way to the door. It teaches the child a) we don’t talk about race and b) that the other person should be embarrassed to have brown skin and it’s unspeakable enough that we should apologize to them for it being pointed out. I have repeatedly heard white people say that’s not what that reaction means, that the kid was just impolite. Y’all. People in minority groups talk about the segments of society all the time. Do you know how many times a day I hear “Is that person Jewish or not Jewish?” from my toddler? Kids of color ask similar questions about the various shades of skin color. There’s nothing impolite or shameful about it unless you act like it is, and that is acting like it is shameful. WASP “politeness” is one of the most powerful tools of white supremacy. (And leads to tone policing.)

That’s overwhelmingly how white people deal with racial conversations in our society, particularly with children who “embarrass us” in public, and it’s how I thought you were supposed to handle those questions! That, friends, is the white supremacist ideology that we breathe like air. NurtureShock was the book that taught me that race must be spoken about openly, matter-of-factly, and frequently. And that non-white parents were already doing this all. the. time. It was really my first “anti-racist book,” even though it’s just one chapter of a much larger book. (The whole book was great, highly recommend.) It was the first book recommended to me by a friend who helpfully (as shocked as I was at the time) pointed out that I had perpetuated white supremacy in a conversation and that it was my responsibility to educate myself. White parents, this is your responsibility too.

Having converted to Judaism as an adult, I see similar minority-majority group discussions in my community and my parenting, though it does come up less frequently because we are white and move through most of American society as white people (my personal white privilege has a lot of intersections with antisemitism but also Islamaphobia since I cover my hair – a practice of many orthodox married women – with a headscarf).

But wait, there’s more!

Now, even after detailing these issues with the book, there’s still another issue. Just reading racist or other bigoted texts to your kids creates implicit bias. The subconscious bias. I can’t recommend the new book Biased enough. My take-away from that (this was my own take-away, not something she said) has been that I need to avoid problematic texts as much as possible until my kids are really old enough to understand and interact with my explanation of it. We see professional advice about avoiding “scary” educational lessons like “climate change might kill us all” until around the fourth grade. Yet we think we’re going to solve the active racism in Little House on the Prairie with our 5 year olds before bed? Really now.

They will get enough exposure to bigoted stereotypes without my help, so I must actively work against this atmosphere of white supremacy and introduce my kids to actively non-bigoted works to make other groups seem, quite frankly, boring and normal. Not amazing super-people. Just everyday people going about life like we do. But it’s still a fine line. Biased goes into research on how positive portrayals of Black characters on TV actually managed to reinforce subconscious negative racial stereotypes anyway. That’s FUBAR.

And that’s before you deal with the lessons unintentionally given when most of your books are populated solely by white drawings, which is another issue the book fails to address. If you sit down and actually count, you would be surprised how many books don’t even have a token person of color in the background (which is a different problem). Instead, the author actively advocates adding more “diverse” books, but should you also be evaluating the number of white-only and white-dominated books you already have? How many books do you have where there are no white characters? (And more broadly, how often are you in situations where white people are not the majority of the people in the room?) That’s the necessary flipside of the “diverse books” question. Diverse books aren’t like an extracurricular add-on activity you do in addition to school, it should be the default of your book collection. And yes, that means you can’t stock every “great book” you see recommended on Facebook because doing so will make your collection way too white. You will have to pick and choose if this is really important to you. And if it’s not important to you, then you need to know that you are perpetuating white supremacy to the next generation.

We’re kind of hosed living in this literal fog of white supremacy that clouds over all our interactions and yes, just about all our books. The best thing white parents of young children can do is to de-segregate your life because odds are that most of you (and me) have lived and are living lives entrenched in (unintentional by you, but very intentional by our history and social structures) segregation. And for more on that, definitely check out Raising White Kids by Jennifer Harvey.

So in other words…

This author’s argument not only fails, it will compound the issue she claims to be solving (did she really think it would be so easy??) and actually make it worse. White parents will feel they have the green light to read problematic texts, with the full good intention of discussing the problems, then they either chicken out in the moment or discuss it in a way that actually makes the problem worse. And the author does not seem to have any of these issues on her radar at all. It would be one thing if she acknowledged them and even said, “you know, I don’t have an answer for that.” Minority parents’ experiences and needs are erased by this book and her answer will unintentionally reinforce another generation of white supremacy. And she doesn’t even know it. Which is kind of the problem of white supremacy and white fragility.

And what books does that leave to read to our younger kids? That’s a different question, and I don’t have great answers. I’m muddling through that myself. And being perfectly honest, I’m usually not thrilled with the literary quality of works that actively try to avoid these issues. And of course, some may actually compound the issue by trying to avoid it. Because…white supremacy. It has its dirty little fingers in everything.

Further Reading:

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Beverly DiAngelo

NurtureShock: New Thinking About Children by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman

Raising White Kids: Bringing Up Children in a Racially Unjust America by Jennifer Harvey

Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice that Shapes What We See, Think, and Do by Jennifer Eberhardt

Leave a Reply